IS ANTI-FASHION STILL ALIVE?

Anti-fashion was prevalent in the 90s and early 2000s, but as conglomerates have become the power player in the industry, its influence has waned. Let's explore.

At its nucleus, fashion has always been about beauty, trendiness, youthfulness, and glamour. From the era of autocracies in Africa and Europe in the early 16th Century up until the major conglomerates of today, elegance has used its iron gauntlet to retain its chokehold on fashion’s global landscape. Then, a new fashion subculture emerged from the abyss of nothingness in the 90s and 2000s - “anti-fashion”.

Anti-fashion can be defined as the intentional non-conformist ideology of rejecting cultural norms of the fashion climate within which one exists. Its design codes intend to challenge conventional ideologies surrounding beauty, are often grotesque in appearance, can be impractical in terms of functionality and wearability, and to many, are bizarre. As with anything that is idiosyncratic, it was met with pushback from the fashion world. However, humans are naturally curious beings, and underneath harsh criticism lay a desire to understand. Anti-fashion made a huge splash and gained its notoriety, but in recent times lost its edge and begun to flicker in the limelight of the cultural zeitgeist.

As anti-fashion is the inverse to standard fashion, its contrarian philosophy follows suit. Since typical fashion is about beauty and glamour, and how clothes interact and mesh with the human body, anti-fashion embodies ruggedness and the rejection of conforming to the human body. The clothes are intended to be a living organism, a beacon of independence. Japanese designer Yohji Yamamoto, a pioneer of anti-fashion, (in)famously stated, “I think perfection is ugly. Somewhere in the things humans make, I want to see scars, failure, disorder, distortion."

This fashion subculture was spearheaded by both Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo (Comme Des Garçons) as they intended to subvert fashion and its inherent meaning. Critics were unimpressed with the style as most did not perceive it as fashion. Some went as far as stating that it was an insult to fashion as an art form. Later in the 2000s, Rick Owens and Martin Margiela followed the approach of the aforementioned Japanese designers, and as time progressed anti-fashion gained popularity and respect from critics and fans alike. Anti-fashion is largely about disruption of the status-quo but not necessarily for the sake of contrarianism, it re-conceptualizes society’s ideological beauty construct. It begs the question, are we still beautiful if we aren’t perfect?

When clothes are seen as a living organism in and of itself, it springs forth undiscovered visions of design codes, whimsical pieces, things that sort of don’t make sense, but are still incredibly entertaining. We begin to see items such as the Hood By Air double-faced cowboy boot, or the Martin Margiela tulle face mask. We even see runway shows like McDonald’s-inspired Vêtements Spring/Summer 2020 collection that hones in on the comical but entertaining element that anti-fashion sometimes tends to portray.

The contemporary fashion industry functions more like a private equity business and less like an artistic communal space - we can all thank Mr. Bernard Arnault for that regression. Every negative outcome in this industry can be primarily connected back to capitalism, and the devolution of anti-fashion and its influence is no exception. Rick Owens, Comme Des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto, Maison Margiela have all somewhat steered away from the core tenets of anti-fashion and now operate in the same vein as their contemporary conglomerate counterparts such as Kering, LVMH, and Prada Group. Rick Owens and Comme Des Garçons participate in the bi-annual fashion calendar, Yohji Yamamoto is a frequent Paris Fashion Week participant and Maison Margiela is now owned by Renzo Rosso’s OTB Group (owners of Marni and Diesel). If a hallmark of anti-fashion is non-conformism, can we still classify these designers who participate in contemporary conformist traditions (major fashion weeks, direct-to-customer selling) as anti-fashion?

However, amid all the commotion of designers supposedly divorcing the ideologies of anti-fashion in exchange for economic sustenance, one designer seems to fight the good fight of faith in his rather controversial taste - that is Carol Christian Poell. Carol Christian Poell (CCP) is an Austrian designer who gained notoriety for his imaginative but rather bizarre design language. Poell attended the Domus Academy School of Design in Milan and shortly after in 1995, founded CCP SRL (SRL means private limited company in Italian) alongside his business partner Sergio Simone.

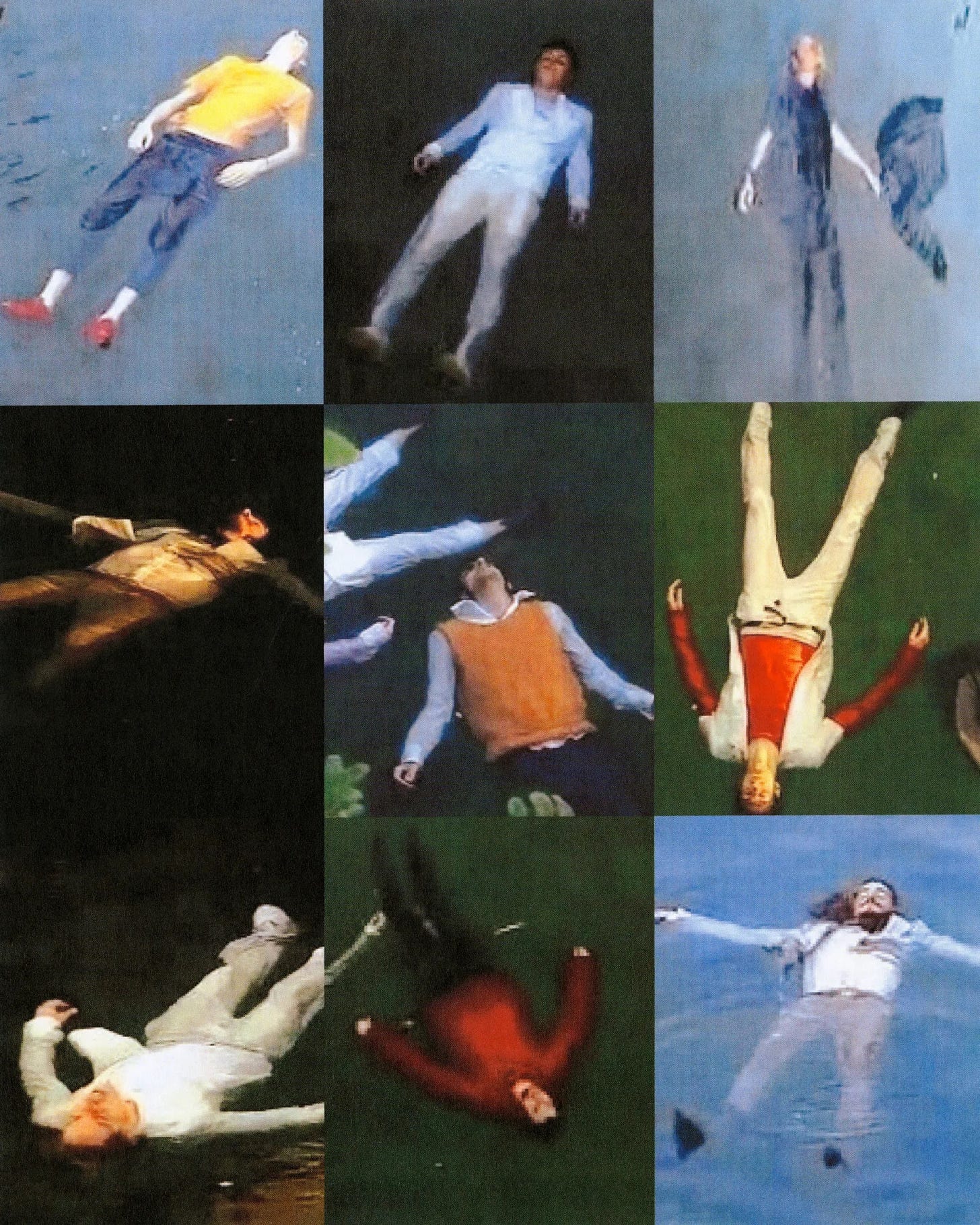

The magnum opus of CCP was the men’s Spring Summer 2004 collection titled “Mainstream Downstream”. It is arguably the most unique presentation of a collection I, and many others have ever stumbled across. The collection included models and items floating down a stream in a canal in Milan. It included some of the most acclaimed CCP pieces such as the rubber twine knitwear sweater, the tornado leather boots, and classic leather jacket. This collection is emblematic of what anti-fashion is in my opinion - taking the codes of contemporary fashion and subverting its meaning to engineer a new context.

On the surface one might say “But if you’ve stripped Rick Owens, Yohji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo of their laurels regarding anti-fashion for showing at fashion weeks, why’s it different for CCP?”. Anti-fashion exists to subvert the concrete blocks of the fashion of its time, it doesn't exist outside it. CCP decided to exhibit its runway show in a canal, as opposed to showing in a cathedral, palace, or a specific esoteric location where the set design adds to the allure of the collection - just like Vêtements did a runway show in McDonald’s!

Now on the more controversial side, CCP is infamous for its more grotesque ideas, designs, and art installations. The most dubious one being the Carol Christian Poell fencing jacket, arguably the most harrowing item of clothing I’ve ever seen. Horses were injected with dye before they were killed, which gave the leather an intentional uneven colour finish. The pig bag made from an entire taxidermied pig in its original form. The metal protection leather jacket has metal implants in the knuckles and elbows that restrict the mobility of the wearer. The dead-end series, which included garments held together by tape or chain seam, designed to appear as if they're being torn apart (they eventually do fall apart as you use them). These and many more items within the CCP cosmos have caused an uproar amongst fashion enthusiasts and advocates for animal rights alike.

Anti-fashion is counterculture, but at what point does it deviate from counterculture and lose its meaning? Has it flown so close to the sun of contrarianism that its core identity has been burned? Or are Carol Christian Poell’s creations meant to make us ponder about the society we partake in? Why is the pig bag grotesque but our consumption of bacon and ham is normalized? Why is the fencing jacket considered bizarre, but cowhide jackets are sought after? Is Carol Christian Poell himself an absurd scientist who has entirely lost the plot or is he holding up a mirror to us and we are hypocrites that cannot see that he’s just an inverse version of us? I like to believe this is what he is ultimately asking. Although I don’t agree with some of his methods, the value of his work supersedes the artistic realm, it is elevated into a philosophical domain.

I don’t believe anti-fashion is dead, I think it’s morphed into a new entity. It’s sort of like energy, - it’s not destroyed, it’s just changed its form. In a period of conventional beauty’s evolution, one which has consistently had white faces and thin bodies at its fulcrum - a new crowd of anti-fashion designers has emerged. Brands such as Greg Ross, Mowalola, and Avavav are again subverting the trendy dogma of Lemaire and Our Legacy. Greg Ross’s clothes feel like they belong to a derelict dystopian society that survived the threat of an intergalactic insurgence. Mowalola is a blend of grunge and chic that exists in a colourful, drug-laden, and fast-paced world. Avavav is like a cosplay of a disorganized university student who is rushing to a 9 a.m. lecture after going to a frat party on a weeknight. All three labels exist under the banner of anti-fashion, but all convey their sensibilities of anti-fashion very distinctly.

Nevertheless, a case can still be made that they are not anti-fashion since they still participate in major calendar runway shows and are stocked by wholesale companies like SSENSE, Harvey Nichols, and Neiman Marcus. On the flipside, a case can be made that anti-fashion is subversion, and subversion exists in different formats. Whether that is the CCP way of shattering the idea of how runway shows should be presented by having models float lifelessly in a canal, or Avavav having models intentionally collapse as they strut the runway to forge panic amongst the fashion press and attendees alike. Subversion isn't a one-way street, it’s got junctions, cul-de-sacs, roundabouts and even untarred roads. It is whatever the designer believes it to be.

So is anti-fashion dead? I’m honestly not so sure. Can something be dead if its successors sustain fragments of its existence? Or is it dead because it isn’t the exact version of what it originally was? Anti-fashion is a spectrum and due to our philosophies, we arrive at a conclusion that aligns. Whether you are closer to the Carol Christian Poell end of the spectrum, or the Comme Des Garçons end, all are emblematic of anti-fashion. Fashion is dynamic and that is one of its strongest suits. It’s glamorous and grungy, flamboyant and filthy, it’s everything all at once. All of its elements work in tandem to inform what end of the spectrum we eventually fall underneath.